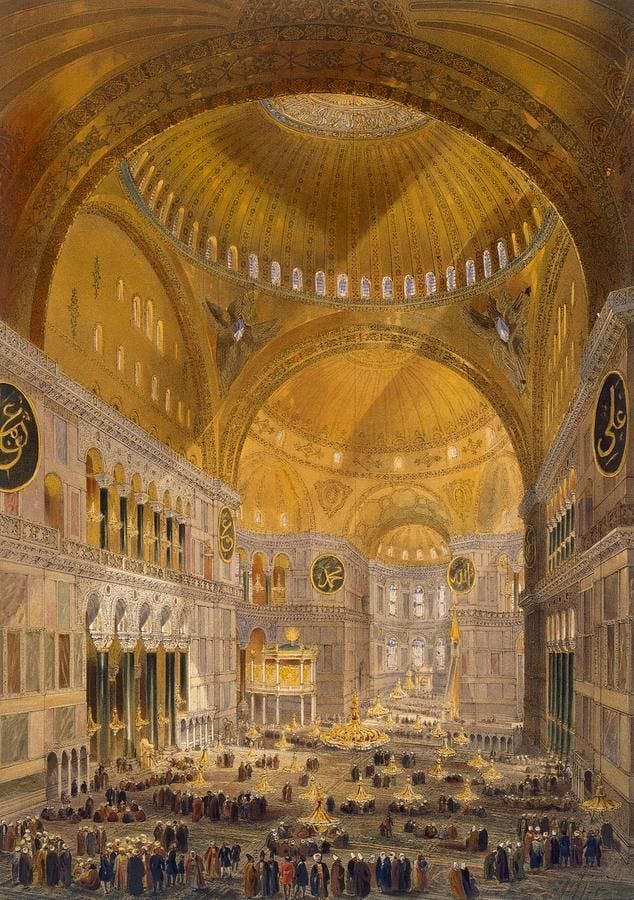

A man once stood before the Dome of the Rock, gazing upon its golden radiance, and declared it the most beautiful building in the world. Yet what he saw was not mere architecture, nor an echo of past grandeur, but something alive—a structure that bore witness to a world infused with meaning, where stone and geometry spoke in the language of the sacred. What force drove those who once wandered the deserts to raise such splendour?

The Beauty of Order, The Order of Beauty

Beauty in Islam was not an indulgence; it was a recognition of divine harmony. Man did not seek to impose order upon the world but to uncover the order that already existed. In the Qur’anic view, the cosmos itself is a vast articulation of balance—mīzān—and in reflecting that balance, Muslim civilisations carved, built, and wrote. And so geometry became a language, calligraphy a meditation, and space itself a canvas upon which the Names of God were inscribed.

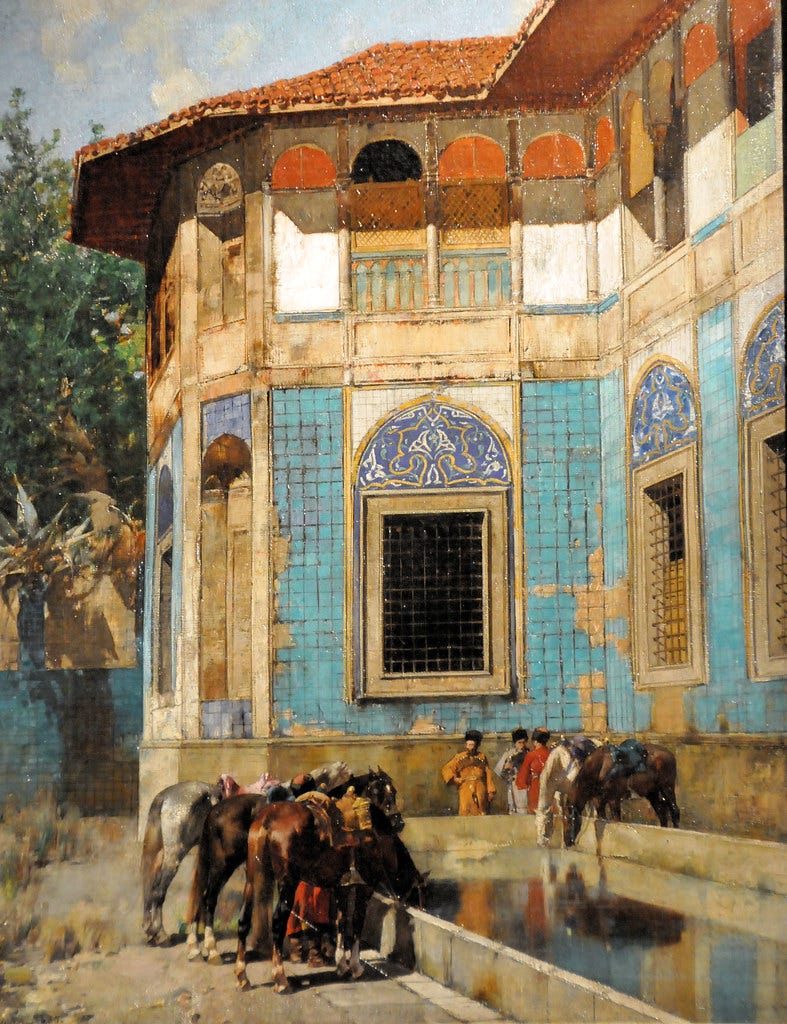

The Ottomans built fountains for the birds and shaded streets for the weary. In Andalusia, the Alhambra’s tessellations reflected paradise not as fantasy but as something possible, something to be mirrored in this world.

Yet this was not merely aesthetic. It was adab—the discipline of placing things in their rightful place, of acting with knowledge, of acknowledging hierarchy, not as an imposition, but as a harmony.

To live with adab was to recognise that every action, every structure, every utterance had its appointed place in the order of things.

And through that recognition, justice emerged—not as an abstraction, but as something lived, something enacted in the smallest of gestures and the grandest of edifices.

The Dignity of the Human Being

If beauty was the face of the civilisation, dignity was its foundation. The Islamic tradition, at its height, did not see the human as a mere participant in the economy, nor as a unit of a bureaucratic state, but as a bearer of divine trust. Khilāfah, vicegerency, was not political alone, but existential—the responsibility to steward, to preserve, to build.

And so, the dignity of the human being was upheld in law and commerce, in governance and daily life. The marketplace was not an arena of unchecked competition, but of fairness, where weights were measured with precision and transactions were built on trust. The traveller was not a foreigner, but a guest with rights over the city. Even those without wealth or status were protected by divine ordinance.

In the modern world, dignity and shame are often placed in opposition, as though self-worth requires the discarding of restraint. But the Islamic tradition knew otherwise: dignity is not found in rejecting limits, but in the refinement of the self within them.

“Verily, ḥayā’ [modesty, self-awareness] and faith go together. If one of the two is missing, so is the other.”

— Hadith

It is a great irony that in a time when shamelessness is celebrated as empowerment. True nobility, as the Prophet ﷺ exemplified, lies not in boastfulness but in humility; not in heedlessness, but in reverence.

To lose ḥayā’ is to lose the internal compass that recognises what is sacred. And when that sense is lost, so too is the impulse to build with meaning, to carve permanence into the world, to leave something behind that is worthy of remembrance.

“God never tries a heart with anything more severe than plucking ḥayā’ from it.”

— Mālik b. Dīnār

Modernity and the Loss of Adab

Muslims have long debated modernity, struggling to define how a civilisation once shaped by sacred order became one marked by fragmentation. There was a time when knowledge was integrated—when the ʿālim was also an astronomer, when the jurist understood the natural sciences, when scholarship was not confined but expansive.

The modern world, however, has collapsed that vision. The speed of change, the erosion of institutions, and the hegemony of secular structures have left many unable to respond, retreating instead into reactionary postures. Beleaguered scholars, disconnected from the intellectual traditions of the past, attempt to address contemporary crises with frameworks unfit for the complexity of the age.

Yet Islam was never meant to be a relic. It does not call for nostalgia, nor for the mere preservation of old forms. It calls for adab, for the restoration of knowledge to its rightful place, for the revival of a world in which beauty and justice, form and meaning, are once again intertwined.

The Restoration of Adab

To lose adab is not merely to lose etiquette—it is to lose the very structure that makes civilisation possible. But the tools for renewal remain.

The great civilisations of Islam did not arise by accident. They were the fruit of a worldview, the outward expression of an inward state. And if today we do not build as they once built, it is not because the materials have vanished. It is because something within us has dimmed.

The same faith that turned deserts into gardens, that lifted stone into light, that saw beauty as justice and justice as beauty, is still here. The question is not whether it has survived, but whether we will see it again—not as nostalgia, but as possibility.

beautifully written!